2012 Year in Review Anna Yin but warn you…

facebook

my jammed friends

we don’t know each other

— ——

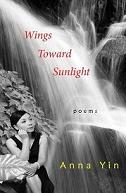

My life in China was normal like the early stage of a butterfly in a cocoon, but passion for poetry bloomed after immigrating to Canada. Although I am an IT professional, mysteriously I have grown wings blending Chinese and Western cultures.

Years later

I am here

The road less travelled

From “Toronto, No More Weeping” to “Root Carving”, I have struggled with the meaning of writing. I almost gave up until I wrote “Farewell to Sunflowers” and found that quitting would have given me a broken heart. I asked myself what I am searching for. As most of us, we all look for some reward. Afterward, I understood that the reward for writing is writing itself. I see that writing builds a path to connect an inner world and the universe.

Today I try my best to embrace the power of “Wings toward Sunlight”; what I see now is that writing is a mirror, reflecting both here and there, a journey to myself and to the world. When reality builds walls, writing breaks through.

“I am just an indifferent fish,

“I am just an indifferent fish,